Project Overview

In early 2022 a young couple bought a modest three-bedroom house on a quiet street in North Hills, just west of Northridge. They loved the neighborhood but knew the monthly mortgage would push their budget to the edge.

Project Details

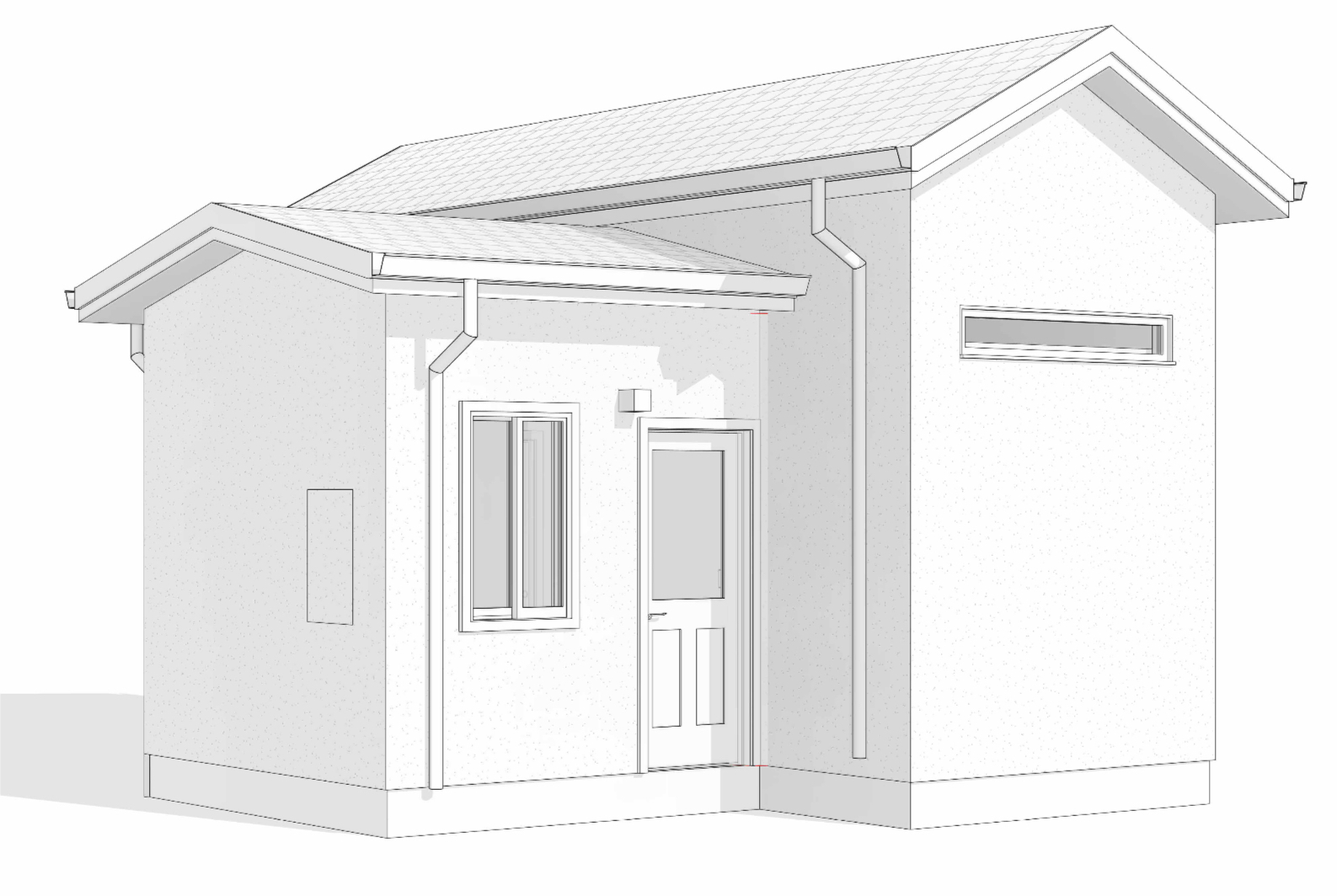

In early 2022 a young couple bought a modest three-bedroom house on a quiet street in North Hills, just west of Northridge. They loved the neighborhood but knew the monthly mortgage would push their budget to the edge. California’s pro-housing laws offered a way out. By adding a detached two-story structure in the backyard—legally classed as a Senate Bill 9 (SB 9) primary unit on the lower level and an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) on the upper—they could create two full-sized rentals, bring in income to cover most of the mortgage, and build long-term wealth at the same time.

From idea to design

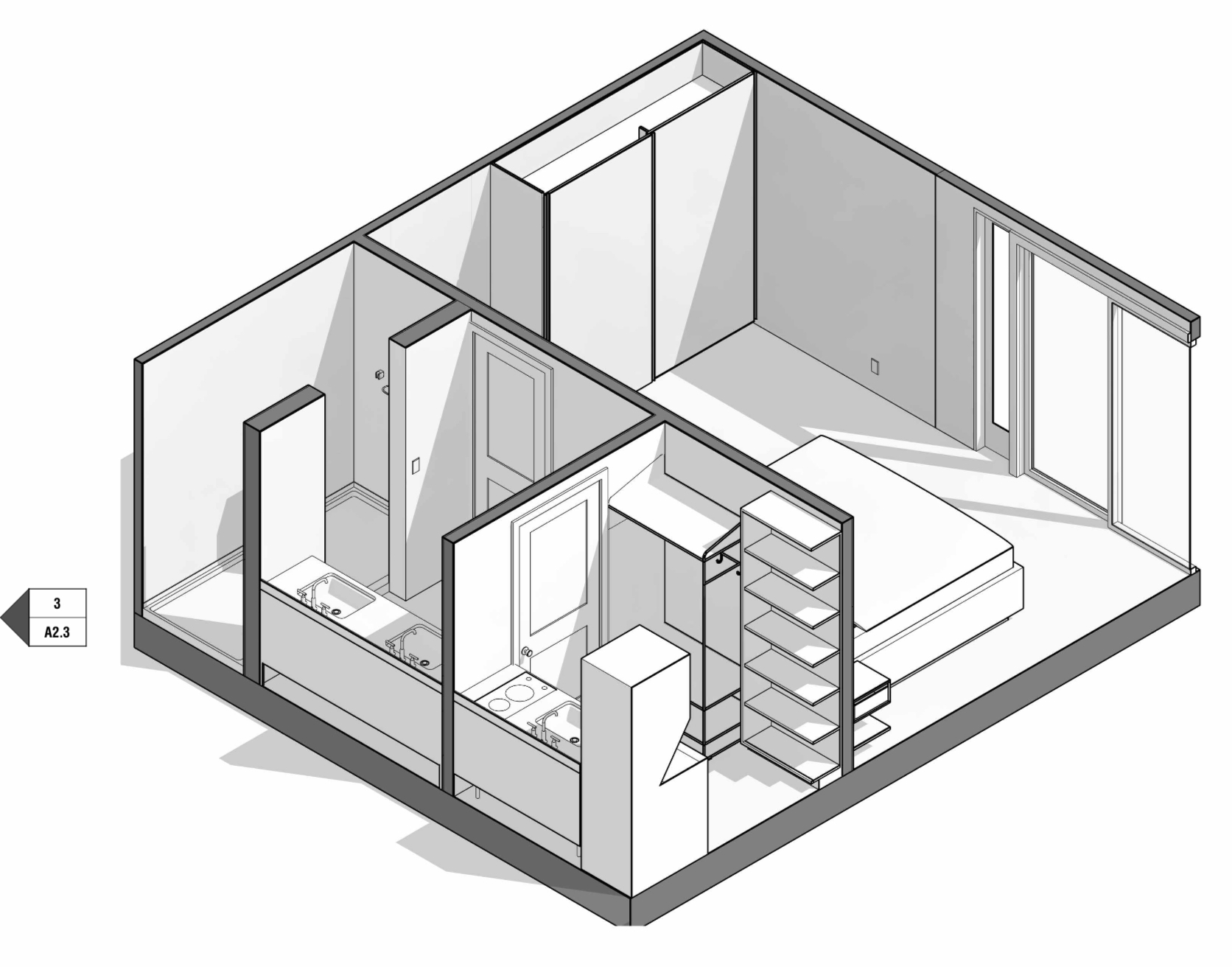

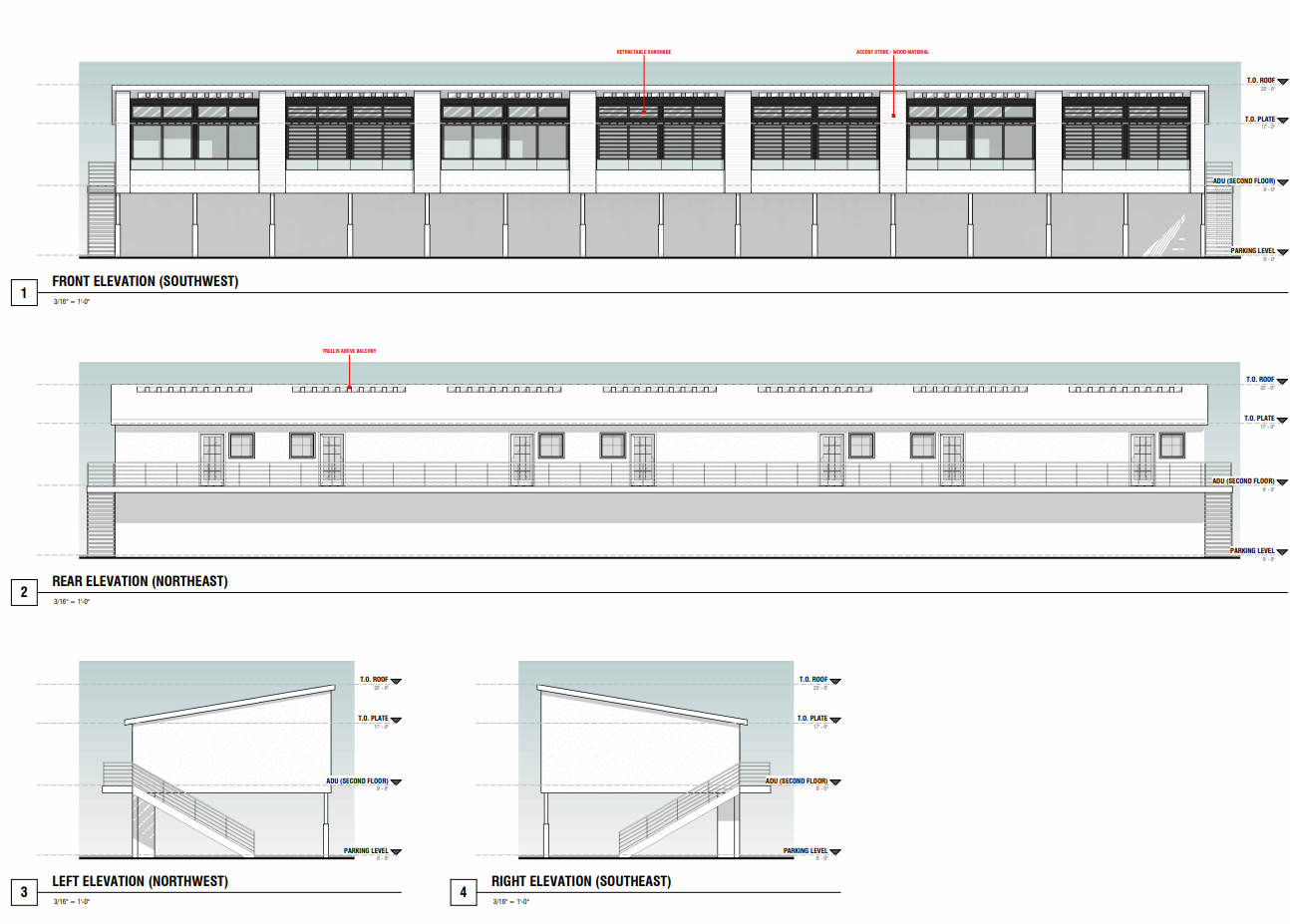

The first step was a zoning check. Within an hour the couple learned their R-1 lot qualified for both an SB 9 split and an ADU. No hearings, no variances, no surprise easements—just a straight-line path to permits. With that green light the project moved to design. Space in the yard was tight, so the architect stacked the homes to preserve outdoor area for all three households. The ground floor became a 1,200-square-foot residence with three bedrooms and two baths. A private exterior stair rose to an 800-square-foot flat above, offering two bedrooms and one bath. Both units would feel completely separate thanks to dedicated front doors, individual mailboxes, their own LADWP electric meters and trash service, and private outdoor entries.

Quality mattered. Quartz counters replaced basic laminate in the kitchens. Bathrooms received full-height subway tile instead of fiberglass surrounds. Energy-efficient windows paired with two-by-six exterior walls and R-21 insulation kept utility costs down. Tankless water heaters saved closet space, and a five-kilowatt solar array trimmed electric bills for tenants and reduced the couple’s operating costs. Outside, drought-tolerant landscaping and a small cedar fence screened each new home from the main house, giving everyone a sense of privacy without wasting water or maintenance budget.

The numbers that drove every decision

Total hard construction—the slab, framing, roofing, stucco, interior finishes, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing—closed at roughly $420,000. Professional design, engineering, and title 24 energy calculations added $20,000. City impact fees, plan-check charges, and inspection costs reached $30,000. Solar panels, fencing, planting, and other extras rounded out another $40,000. All-in the couple spent about $510,000.

Rentals in this part of the Valley command solid prices, especially for modern, move-in-ready units with separate utilities. Comparable three-bedroom homes were leasing near $3,800 per month, while fresh two-bedroom ADUs fetched around $3,000. Before construction wrapped, the couple began marketing photos online and held showings during the final punch-list week. Within eleven days signed leases hit the inbox: $3,850 for the ground-floor three-bedroom, $2,950 for the upstairs two-bedroom. Tenants pay their own electric, gas, and water because of the separate meters. Gross scheduled rent now stands at $6,800 each month—money that almost erases the original mortgage and leaves room for reserves and future upgrades.

Operating expenses for taxes, insurance, maintenance, and a small management fee absorb roughly 27 percent of that rent. After those costs the couple nets about $4,900 per month. In practical terms one backyard project turned a stressful mortgage into comfortable positive cash flow less than two years after buying the property.

.jpg)

What the property is worth today

Before any work began, local sales data placed the house at roughly one million dollars. Adding 2,000 square feet of new, fully permitted living area—together with the proven rental income stream—changed everything. Based on recent closed sales of similar tri-plex setups in North Hills and Northridge, a conservative market estimate now values the entire parcel near $1.6 million. Even after subtracting the $510,000 build cost, the couple gained about $100,000 in fresh equity the day tenants moved in, and their debt-to-income ratio flipped from tight to comfortable.

A fourteen-month timeline

Design and engineering took barely two months, thanks to clear zoning rules and fast owner feedback. Plan check with Los Angeles required five months; thorough drawings meant all corrections were cleared in the first resubmittal. Six months of construction followed, broken into four tight phases: sitework and slab, panelized framing, mechanical-electrical-plumbing rough-ins, and finishes plus landscaping. The final month overlapped inspections, punch-list fixes, utility sign-offs, and lease-up. Not a single week was wasted.

Challenges and quick fixes

No construction project runs perfectly. Mid-way through framing, lumber prices jumped fourteen percent. Because the builder had locked material contracts at the start, the spike hit the lumber yard—not the couple. During stucco work a weekend compressor irritated a next-door neighbor; the crew shifted noisy tools to weekdays and erected dust screens, ending the complaint. Black-frame windows suffered a ten-week factory delay industry-wide, yet early ordering—placed while plans were still in plan check—meant those windows arrived exactly when installers needed them. Problems surfaced, but quick communication and written action items kept the schedule intact and prevented costly change orders.

Why separate utilities were worth it

Running individual 200-amp panels to each unit added a few thousand dollars and an extra LADWP inspection. That step paid back immediately. Tenants appreciate paying only for their own use, which reduces billing disputes and encourages responsible energy habits. More importantly, lenders and appraisers treat separately metered units like standalone apartments, which pushes valuation higher than a property with shared utilities. For the couple, the meters were not a luxury—they were an equity and financing tool.

Long-term outlook

Rental demand in the northwest San Fernando Valley shows no sign of slowing. Year-over-year market data point to steady rent growth near three percent. Even if rents stayed flat, the couple’s net income already covers the mortgage, funds maintenance reserves, and leaves monthly surplus they now route into an index fund. Over the first ten years the principal balance on the original home loan will drop while rents likely rise, compounding the wealth effect.

On the environmental side, the five-kilowatt solar array offsets roughly seven metric tons of carbon dioxide every year—the equivalent of planting around 120 mature trees. Drought-tolerant landscaping slashes outdoor water use by about 70 percent. The new construction meets California’s 2022 Energy Code, meaning better insulation, tighter ducts, and lower operating costs compared with the 1950s-era main house.

Lessons for other homeowners

This project highlights a few takeaways for any owner thinking about an ADU or SB 9 build:

- Verify zoning early. A one-hour code check prevents months of redesign.

- File SB 9 and ADU plans together. Parallel processing shortens city review.

- Order long-lead items upfront. Windows and HVAC equipment can bottleneck a schedule.

- Invest in durable finishes. Higher upfront costs save thousands in turnover repairs later.

- Separate the utilities. It simplifies tenant life and boosts property value.

- Walk the site weekly. Small issues caught early never grow into budget-busters.

.jpg)

The bigger picture

Two new, code-compliant homes now stand where an unused garage and a patch of grass once sat. The city gained much-needed housing without paving fresh land. Local trades logged more than four thousand paid labor hours. The streetscape looks sharper, the owner’s financial stress is gone, and long-term equity has already climbed six figures.

Success like this is not just for developers or retirees with decades of savings. A young couple, only months into home ownership, unlocked the power of their lot by combining smart design, careful budgeting, and the latest California housing laws. Their experience proves that the right plan—executed with discipline—can turn backyard square footage into real financial freedom, long before the thirty-year mortgage clock runs out.

Our Approach

Discovery & Planning

We analyzed the property, zoning regulations, and homeowner goals to create a customized feasibility plan.

Design

Our designers created custom floor plans maximizing space while respecting the budget and aesthetic preferences.

Permitting

We navigated city requirements and handled all paperwork, securing permits efficiently.

Construction

Our licensed contractors brought the ADU to life with premium materials and meticulous attention to detail.

Understanding ADUs

An accessory dwelling unit that provides independent living quarters with kitchen, bathroom, and sleeping facilities. This project in Los Angeles exemplifies the benefits and possibilities of this ADU type, demonstrating how homeowners can maximize their property's potential while creating valuable living space.

Key Benefits

Ideal For

Los Angeles ADU Market Insights

Los Angeles is located in Southern California and represents one of the most dynamic ADU markets in the area. With a population of 3.9 million and median home prices of $950,000, the demand for accessory dwelling units continues to grow as homeowners seek to maximize their property value and generate additional income.

Why Build an ADU in Los Angeles?

ADU Investment Potential in Los Angeles

Building an ADU in Los Angeles represents a significant investment opportunity. Based on current market conditions and rental rates in the Southern California area, homeowners can expect strong returns on their ADU investment. The combination of high rental demand, favorable regulations, and property value appreciation makes this an attractive option for long-term wealth building.

Investment Note: ADUs in Los Angeles typically pay for themselves within 8-12 years through rental income alone, while also providing immediate property value appreciation. Many homeowners also benefit from tax advantages and depreciation deductions.

Typical ADU Building Timeline in Los Angeles

Understanding the ADU construction timeline helps homeowners plan effectively. Here's what to expect when building a adu in the Southern California area.

Feasibility & Design

2-4 WeeksSite analysis, zoning verification, initial design concepts, and cost estimation. We assess your property's ADU potential and create preliminary plans.

Architectural Plans

3-6 WeeksDetailed architectural drawings, structural engineering, Title 24 energy compliance, and complete permit-ready documentation.

Permitting

8-16 weeksPermit application submission, plan check review, and approval process. Los Angeles offers streamlined ministerial review for qualifying ADU projects.

Construction

4-10 monthsFoundation, framing, MEP rough-in, insulation, drywall, finishes, and final inspections. Our licensed contractors manage every phase with quality craftsmanship.

Final Inspection & Move-In

1-2 WeeksCertificate of occupancy, utility connections, final walkthrough, and handover. Your ADU is now ready for occupancy or rental.

Ready to Start Your ADU Project in Los Angeles?

Get expert guidance on designing and building your own accessory dwelling unit. Our team specializes in Southern California ADU projects.

ADU Regulations in Los Angeles

Understanding local ADU regulations is crucial for a successful project. Los Angeles follows California state ADU laws while implementing local standards. Here are the key regulations that applied to this project and similar builds in the area.

Size Limits

- Detached ADU: Up to 1,200 sq ft

- Attached ADU: 50% of primary home

- JADU: Up to 500 sq ft

- No minimum size requirement

Setbacks

- Rear setback: 4 feet minimum

- Side setback: 4 feet minimum

- No front setback for JADUs

- Conversions: Existing setbacks apply

Height Limits

- Detached: 16-18 feet typical

- 2-story ADUs: Up to 25 feet

- Must not exceed primary dwelling

- Local variations may apply

Parking

- No parking within 1/2 mile of transit

- Garage conversions: No replacement

- JADUs: No parking required

- Tandem parking allowed

Pro Tip: California's ADU laws are updated regularly. Our team stays current on all local and state regulations in Los Angeles to ensure your project meets current requirements and takes advantage of all available streamlining provisions.

Frequently Asked Questions About ADUs in Los Angeles

How much does it cost to build an ADU in Los Angeles?

ADU costs in Los Angeles typically range from $80,000 for garage conversions to $350,000+ for larger detached units. Factors affecting cost include size, finishes, site conditions, and utility connections. Based on current market rates, a typical adu like this project costs approximately $120,000-$300,000.

How long does it take to get ADU permits in Los Angeles?

Los Angeles currently processes ADU permits in approximately 8-16 weeks. California law requires cities to approve or deny ADU applications within 60 days. Many jurisdictions, including Los Angeles, offer expedited processing for standard designs and pre-approved plans.

What is the rental income potential for an ADU in Los Angeles?

Based on current market rates in Southern California, a 1-bedroom ADU can rent for approximately $2,400/month, while 2-bedroom units command around $3,100/month. This translates to an estimated annual return of 4.2% on your investment.

Do I need to live on the property to build an ADU in Los Angeles?

California law prohibits cities from requiring owner-occupancy for ADU permits. You can build an ADU on your property regardless of whether you live there. However, some financing options may have occupancy requirements, and short-term rental rules vary by location.

Can I Airbnb my ADU in Los Angeles?

Short-term rental regulations vary by city and neighborhood. Los Angeles has specific rules governing vacation rentals that may require registration, permits, or occupancy requirements. We recommend consulting local regulations and our team can help you understand the options for your specific property.

ADU Services in Nearby Southern California Areas

GatherADU provides comprehensive ADU design and construction services throughout Southern California. We serve homeowners in Los Angeles and surrounding communities with the same expert guidance and quality craftsmanship demonstrated in this project.

Whether you're considering a adu like this project or exploring other ADU options, our team understands the unique characteristics and regulations of each neighborhood in the Southern California area. Contact us to discuss your specific property and goals.

Helpful ADU Resources

Explore our comprehensive ADU resources to learn more about the process, costs, regulations, and design options available to you.

Ready to Build Your Dream ADU?

Let's discuss how we can help you create additional living space, generate rental income, or provide housing for loved ones.