When families start exploring options for adding living space to their property, two terms come up again and again: mother-in-law suite and ADU. Sometimes people use them interchangeably, which only adds to the confusion. But these are actually distinct concepts with different implications for your project, your budget, and your long-term options.

I've walked dozens of families through this decision. Some come in convinced they want one thing and leave realizing the other makes more sense. There's no universally right answer. The best choice depends on your specific situation, your property, and what you're hoping to accomplish.

Let me break down the real differences so you can make an informed decision.

Defining Our Terms

A mother-in-law suite is really a functional description rather than a legal category. It refers to any private living space designed for a family member, typically including a bedroom, bathroom, and some kitchen facilities. The name obviously comes from the traditional use case of housing a spouse's mother, though these spaces serve all kinds of family members.

An ADU, or Accessory Dwelling Unit, is a legal classification defined by California state law. It's a complete, self-contained living unit with its own entrance, full kitchen, bathroom, and sleeping area. ADUs must meet specific building codes, go through a formal permitting process, and can legally be rented to anyone.

Here's where it gets interesting: a mother-in-law suite can be built as a permitted ADU, but it doesn't have to be. And that choice has significant consequences.

The Permitting Question

When you build a permitted ADU, you're creating a legally recognized dwelling unit. This means going through your local planning department, getting building permits, passing inspections, and ensuring the space meets current building codes for things like egress windows, ceiling heights, electrical systems, and plumbing.

Some mother-in-law suites are built without going through this full process. Maybe they started as a basement remodel that gradually became more self-contained. Maybe a homeowner added a kitchenette to an existing guest room. These spaces exist in a legal gray area.

The unpermitted route might seem easier in the short term, but it creates real problems:

- You can't legally rent the space to non-family members

- Insurance claims may be denied if something happens in an unpermitted space

- When you sell your home, unpermitted additions can kill deals or require costly corrections

- Safety standards may not be met, putting occupants at risk

California's recent ADU legislation has made the permitting process much easier than it used to be. Cities are required to approve compliant applications within 60 days, and many have streamlined the process significantly. The extra effort of doing things properly almost always pays off.

Flexibility and Future Options

This is probably the biggest practical difference between the two approaches, and it's worth thinking about carefully.

A permitted ADU can serve any purpose you want. Use it for your mother-in-law today, rent it to a tenant tomorrow, let your adult child live there next year, or turn it into a home office when circumstances change. The legal status remains the same regardless of who occupies it.

An informal mother-in-law suite built without ADU permits is essentially locked into family use. The moment you try to rent it out, you're potentially violating local housing codes and putting yourself at legal risk. This limits your options if your situation changes.

I've seen families regret the informal approach when circumstances shifted. Parents passed away or moved to assisted living, adult children found their own places, relationships changed. Suddenly they had a space they couldn't legally monetize, sitting empty or underutilized.

According to a UC Berkeley Terner Center study, ADU owners who rent their units earn an average of $1,000 to $2,500 per month depending on location and size. That's significant income that's simply not available if you didn't go through the proper channels.

Cost Comparison

Let's talk money, because that's often the deciding factor for families weighing their options.

A basic mother-in-law suite conversion, like adding a bathroom and small kitchen area to an existing bedroom, might cost anywhere from $30,000 to $80,000 depending on the scope of work and finishes. This is the most affordable route, especially if you're working with an existing space that needs minimal structural changes.

A fully permitted ADU costs more. Garage conversions typically run $100,000 to $200,000 in Southern California. New detached construction ranges from $200,000 to $400,000 or more. These numbers include permits, professional design, code-compliant construction, and all the finishes.

But here's the thing: you need to think about this as an investment, not just an expense. That permitted ADU adds significant value to your property. Appraisers recognize it as additional square footage with rental potential. Buyers will pay a premium for a property with a legal ADU compared to one with an unpermitted in-law space.

| Cost Factor | Basic In-Law Suite | Permitted ADU |

|---|---|---|

| Construction Cost | $30,000 - $80,000 | $100,000 - $400,000 |

| Permit Fees | Minimal or none | $5,000 - $15,000 |

| Design/Architecture | Optional | $5,000 - $15,000 |

| Property Value Increase | Moderate | 20-30% of ADU cost |

| Rental Income Potential | None (legally) | $1,000 - $2,500/month |

Privacy and Independence Considerations

The level of separation between spaces matters a lot for daily life. Both mother-in-law suites and ADUs can offer privacy, but the typical configurations differ.

Many mother-in-law suites are interior spaces connected to the main house. Maybe it's a converted basement with an internal staircase, or a wing of the house that's been given its own bathroom and kitchenette. These configurations keep family members close, which is great for caregiving situations but can feel cramped for everyone involved.

ADUs, by definition, have their own separate entrance. They function as independent homes, even if they're attached to the main house. This physical separation often makes a big difference in how comfortable everyone feels with the arrangement.

I've talked with many families who started with an interior in-law suite and later converted it to a proper ADU with a separate entrance. The added privacy improved relationships and made the living situation sustainable long-term.

Building Code Requirements

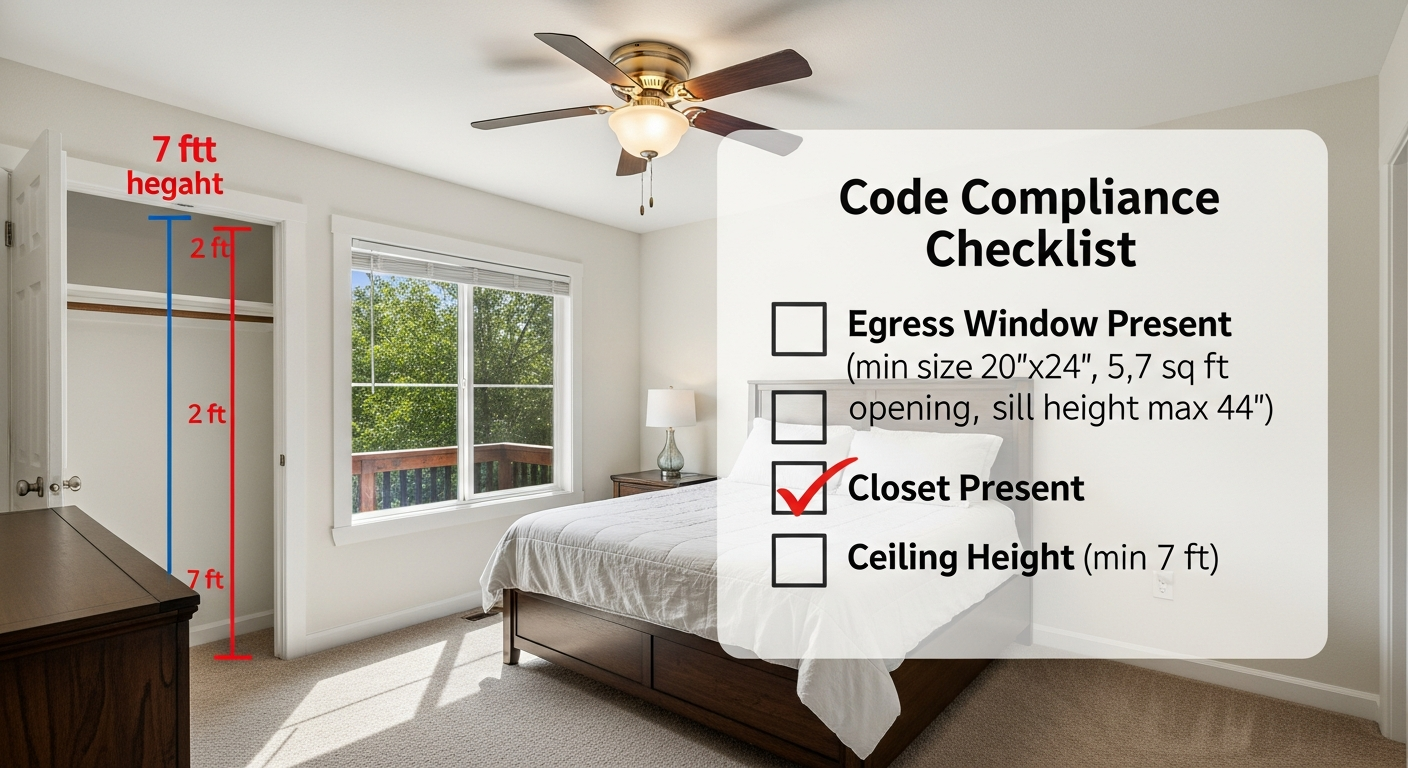

California's building codes exist to protect occupants. When you build a permitted ADU, you're ensuring the space meets these safety standards:

Egress requirements specify that bedrooms must have windows large enough for emergency escape. This isn't just bureaucratic red tape. It's the difference between your family member being able to escape a fire and being trapped.

Electrical and plumbing codes ensure systems can handle the load and won't cause fires or water damage. Older homes especially may need panel upgrades or plumbing modifications to safely support an additional unit.

Ventilation requirements in kitchens and bathrooms prevent mold and maintain air quality. Proper insulation keeps the space comfortable year-round without excessive energy costs.

Informal mother-in-law suites often cut corners on these requirements, either intentionally or through ignorance. The result can be spaces that are uncomfortable, inefficient, or genuinely dangerous.

When a Mother-in-Law Suite Makes Sense

Despite everything I've said about the advantages of permitted ADUs, there are situations where a simpler in-law suite is the right choice.

If you already have an extra bedroom with an attached bathroom and just want to add a mini-fridge and microwave, you're not really creating a new dwelling unit. You're just making a guest room more comfortable. This level of modification typically doesn't require ADU permits.

If you're dealing with a very short-term situation, maybe a parent recovering from surgery who will return to their own home in a few months, the investment in a full ADU may not make sense.

If your property has severe constraints that make a permitted ADU impractical or impossible, improving an existing space might be your only option. Though I'd encourage you to consult with a professional before assuming you can't build an ADU. Many homeowners are surprised by what's actually possible.

When an ADU Is the Clear Winner

For most families I work with, a permitted ADU is the better long-term choice. It's especially compelling when:

You want the option to rent the space now or in the future. The rental income potential is substantial and can help offset your investment.

You're building new construction or doing a major renovation anyway. If you're already going through a permitting process, adding ADU compliance often isn't much more work.

Privacy and independence are priorities for everyone involved. That separate entrance makes a real difference in daily life.

You're thinking about resale value. A legal ADU is a significant selling point that can justify a higher asking price.

Not Sure Which Option Is Right?

Every property and family situation is unique. We can help you evaluate your options and understand what's possible on your specific lot.

Call us at (323) 591-3717 or schedule a free consultation to discuss your project.

The Hybrid Approach

Here's something that comes up often: families who want to start with something simple and potentially upgrade later. This can work, but you need to plan for it.

If you're building a basic in-law space now with the intention of converting it to a full ADU later, make sure you're not creating obstacles for the future conversion. Things like electrical panel capacity, plumbing rough-ins, and structural considerations can be addressed in the initial work even if you're not going all the way to a permitted ADU right now.

Talk with a builder who understands ADU requirements before you start any work. They can help you make decisions that keep your options open without necessarily committing to the full ADU cost upfront.

Making Your Decision

The choice between a mother-in-law suite and an ADU isn't really about the names. It's about how much you want to invest, how much flexibility you want for the future, and how formally you want the space to be recognized.

For most families thinking long-term, I recommend going the ADU route. Yes, it costs more upfront. Yes, it requires more planning and paperwork. But the flexibility, the rental potential, the property value increase, and the peace of mind that comes from doing things properly usually justify the investment.

If you're genuinely just making minor modifications to an existing space for short-term family use, a simpler approach may suffice. But be honest with yourself about your situation and your future needs.

Either way, I'd encourage you to have a conversation with a professional before committing to a path. Understanding what's possible on your specific property, given your budget and goals, is the first step toward making the right choice for your family.

Sources cited:

- UC Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation. (2022). "ADU Owner and Renter Survey Findings."

- California Department of Housing and Community Development. (2023). "Accessory Dwelling Unit Handbook."